Chicago is the ever-beating architectural heart of America: From developing the modest balloon-frame home to creating the skyscraper, Chicago architecture is the birthplace of some of the most iconic and groundbreaking buildings the country has ever seen.

Our access to the natural resources of the Midwest provided ample building materials, including timber from Michigan, limestone from Indiana and Joliet, Illinois, and bricks from quarries in suburbs to the south and west. Chicago grew from a log fort near Lake Michigan and the mouth of the Chicago River to a bustling mid-19th-century metropolis, only to see much of the city destroyed in two days in the Great Fire of 1871.

The Chicago architects who rebuilt the city were astonishingly innovative, with advancements in engineering like fireproofing and modern skeletal steel construction, as were the working-class immigrants who created our local residential styles, the backbone of our housing stock. The end result? Chicago is a city of supertall skyscrapers and belts of bungalows—and both are equally important to its narrative.

While no list can include everything, here is a sample of Chicago’s defining architectural styles and types—and how to identify them.

1. Chicago School

This bold commercial style of architecture emerged a decade after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, as the buildings constructed immediately after the city’s rapid rebuild became unsuited to supporting the flourishing downtown. The Chicago School was a culmination of timely and groundbreaking engineering techniques, such as the introduction of the hydraulic elevator, which made it possible to extend a building’s height over six stories. Improved techniques in foundation construction also helped architects take building to new heights on the swampy Chicago ground, and steel frameworks replacing iron skeleton construction made the skyscraper possible—these steel and glass structures were flexible in terms of floor plan and virtually fireproof.

But it was the details and flourishes—the artistic consideration—of these tall buildings that made the Chicago School iconic. Architects like Burnham & Root and William Le Baron Jenney added delicate natural forms to the interiors, adorning the cornices and entrances with flowers, leaves, wreaths and ribbons. Louis Sullivan took those same forms and upgraded them by adding geometric shapes, covering facades with lacy roulette curves.

HOW TO IDENTIFY: Buildings of the Chicago School can be singled out by their stocky appearance, substantial height, masonry cladding, and decorative cornices. Many feature Chicago windows, fixed central glass panels flanked by two narrower glass sashes, filling bays that are often repeated horizontally and vertically.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: Reliance Building (Burnham & Root, Charles B. Atwood), Monadnock Building (Burnham & Root), Carson Pirie Scott & Company Building (Louis Sullivan)

2. Workers Cottage

An 1883 advertisement, printed in both English and German, refers to these homes as the “Handsomest Brick Cottages in Chicago.” For the ones that remain, it’s still true. Originally built in working- and middle-class neighborhoods across Chicago, workers cottages are modestly scaled and sized, often with gabled roofs and side-set front entrances balanced by windows. While the form changed little over time, they were easy to decorate with turned Italianate details below the roofline or around the doorway, or with carved limestone lintels and panels of art glass. Flexibility and affordability have served the workers cottage well over time, allowing owners to make changes based on fashion or need, cladding many in permastone or adding colorful awnings.

HOW TO IDENTIFY: Workers cottages are generally identified by their small size and front-facing gable, and may be one or two stories, with the first often below street level. Because of their size and general affordability, workers cottages have always been flexible to the needs and wants of their occupants, making the age and type of decoration, and even cladding material and windows, a cross-section of materials across time.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: Workers cottages are located in neighborhoods like Bridgeport, Back of the Yards, Old Town, Tri-Taylor, and Pilsen.

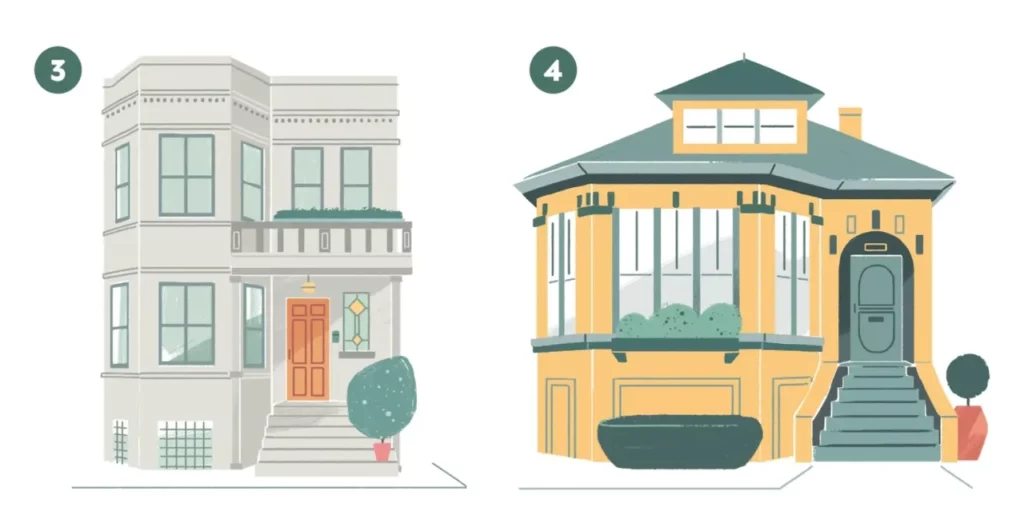

3. Greystones

The greystone could be Chicago architecture in its truest, most homegrown form, representing the city’s transition out of the rapid utilitarian rebuilding after the Great Fire of 1871 and into the energy generated around the 1893 World’s Fair; it marked the move from reactive post-fire building into proactively trying to upgrade the city’s design as it got more of the world’s attention. While it is not strictly a style but more of a common type, the greystone is so ubiquitous in Chicago that it deserves its own category, despite the fact that it’s built in various styles, like Romanesque Revival, Prairie Style, and Queen Anne.

The primary material for Chicago greystones comes from a belt of Mississippian-era Salem limestone near Bedford, Indiana, almost 250 miles south of the city limits. Its moody grey hue is remarkably consistent in color—it’s also incredibly durable. Greystones can withstand Chicago’s harsh winter but will also accept elaborate carvings, as seen on the Dewes Mansion in Lincoln Park, or be finished with a uniform smoothness, or rustication. Greystones are present in practically every neighborhood, from Logan Square to Garfield Park and Woodlawn, as homes for the elite or flats for Chicago’s working class.

HOW TO IDENTIFY: The Chicago greystone is generally identified by the color of the gray rock it is known for, often installed as large rectangular or square bricks, which can be smooth or rough and natural. It could have a highly decorated exterior or look simple with no ornamentation. Most are either two- or three-flat buildings which have a unit on each floor.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: Swift Mansion, the King-Nash House, the Dewes House, and throughout the North Lawndale neighborhood

4. Bungalows

Bungalows are quintessentially Chicago architecture. They are so common that entire blocks filled with bungalows were marked as ineligible for landmark status when the city surveyed neighborhoods between 1983 and 1994. Now, this type is protected by 13 different historic districts listed on the National Register of Historic Places. With many bungalows concentrated in a collar just around the city limits, they make up a third of Chicago’s single-family housing stock, and continue to appeal to the middle class, just as they did in the early 20th century. Chicago bungalows are defined by low-pitched roofs with wide overhangs—a design distinction that has become threatened as homeowners add full-size second floors, or “pop-tops.”

HOW TO IDENTIFY: The Chicago bungalow is characterized by its expansive front facade, low-pitched roof, and wide overhangs, all topped with a symmetrical dormer window. Bungalows are often one and a half stories over a basement, with a large window bay up front and a side-set entrance. While the floorplan has few deviations, bungalows can be clad in almost any material, from brick to terra cotta, and feature design elements inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement or other more classical styles.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: Bungalows are located in neighborhoods like Brainerd, Chatham, and Belmont Cragin.

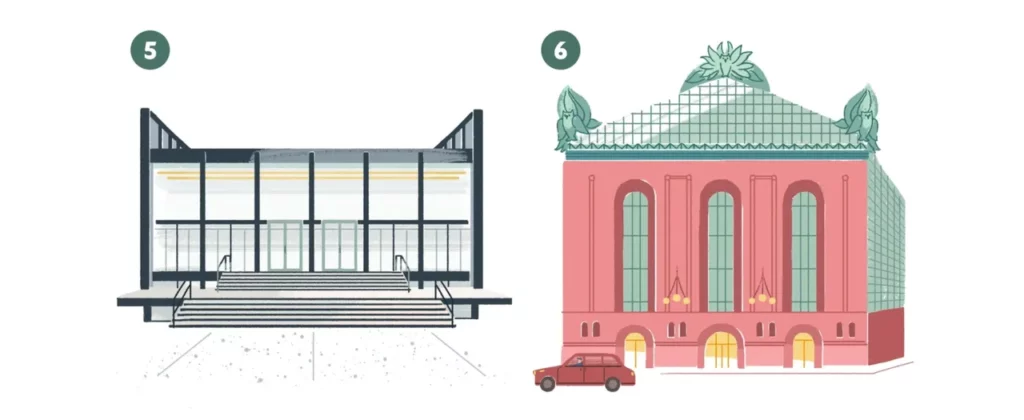

5. International Style/Miesian Modern

When Ludwig Mies van der Rohe arrived in Chicago after fleeing Nazi Germany in 1938, the Illinois Institute of Technology was still the Armour Institute, with classes held in a beefy Romanesque terra-cotta castle. By the 1960s, Mies had developed a new style at IIT and in Chicago (we have more of Mies’s designs than any other city), and cleared the way for other architects to break from the prewar Chicago model and build structures skinned in glass and steel. Miesian influence—what became Miesian Modern—runs the gambit between the understated IBM Building, the sleek towers the architect himself designed at 860-880 North Lake Shore Drive, and low angular buildings on IIT’s campus.

HOW TO IDENTIFY: An authentic International Style/Miesian Modern building has the goals of hitting proportion and scale out of the park within a grid rendered in steel and glass. That original formula was copied on by corporate America, creating the many steel and glass boxes we know today, which don’t hue to strict Mies principles. The purest buildings of this style expose the simplicity of their design, and tend to have good posture, like they are posing for a picture with their hands on their hips.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: 860-880 North Lake Shore (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe), S.R. Crown Hall (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe), Inland Steel Building (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill)

6. Postmodernism

The postmodernism of Chicago architecture is inspired by the future and the past, but also by its own historic landmarks. There is the abstractly patriotic James R. Thompson Center, pulling from classical forms in form but goofing around with its function, as this is a government building that is also a mall (or is it a mall that is a government building?). At the Harold Washington Library, a glass and aluminum roof is covered in elaborate metal twisties, including giant owls clutching books with their talons, palmettes, and Sullivanesque flourishes all about to take flight above a layer cake of architectural styles. In far northwestern Dunning, architect Bertrand Goldberg designed a high-tech pyramid for Wright College as a new campus of the City Colleges of Chicago in 1992. The cheekiest of all might be Stanley Tigerman’s 60 East Lake Street, a self-park garage that doesn’t look like a garage, but the front end of a luxury car.

HOW TO IDENTIFY: Postmodernism is defined by its unusual shapes, creative uses of color, and plays on architectural tradition. They may explicitly express their use, for example a parking garage that looks like a car, or may have architectural components that are off their axis or upside down. Postmodern architecture revolted against the clean lines of the International style, so be on the lookout for the opposite of “less is more.”

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: James R. Thompson Center (Helmut Jahn), 60 East Lake Shore Drive (Stanley Tigerman), Harold Washington Library (Hammond, Beeby & Babka), Wright College Library (Bertrand Goldberg)

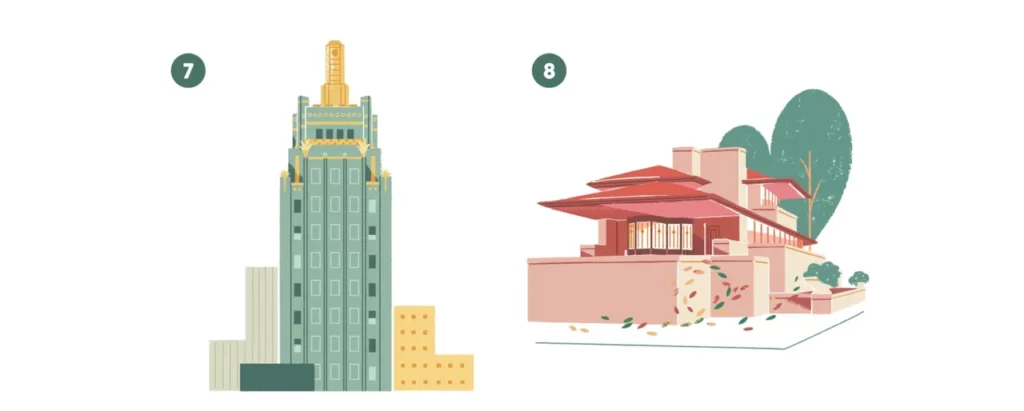

7. Art Deco

At the foot of the LaSalle Street canyon sits the streamlined, stepped Chicago Board of Trade Building. Completed in 1930 and designed by Holabird & Root, the firm responsible for many of Chicago’s Art Deco Landmarks, the structure is topped with an enormously scaled 40-foot-tall statue of Ceres, the goddess of grain. While many of Chicago’s Art Deco structures are of Indiana limestone, the skyrocketing tower of the Carbide & Carbon Building is clad in army green terra cotta and finished with 24-karat gold accents, purportedly to resemble a Champagne bottle. Art Deco arrived in neighborhoods like the Polish Triangle later, with small commercial storefronts like the Starsiak Clothing Building, constructed in 1936, and the Chicago Bee Building in Bronzeville, which is now a Chicago Public Library Branch.

HOW TO IDENTIFY: Clean, streamlined lines dominate Chicago Art Deco. Both the building’s shapes and ornamentation reach upward, creating vertical silhouettes that are often rendered in contrasting terra cotta.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: Carbide & Carbon Building (Burnham Brothers), Chicago Board of Trade Building (Holabird & Root), Civic Opera Building (Graham, Anderson, Probst & White), Palmolive Building (Holabird & Root), Starsiak Clothing Building (Architect Unknown), Chicago Bee Building (Erol Z. Smith).

8. Prairie School

While Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett were looking toward the classical architecture and harmonious public spaces of European cities to create their Plan of Chicago in 1909, Frank Lloyd Wright was designing a dramatically cantilevered new home for Frederick C. Robie in Hyde Park. Wright’s designs created a radical “New School of the Middle West” that historians would later christen the Prairie School, defined by broad, low eaves, horizontal lines, and a rejection of historical styles. Architecture firms like Wright’s, George W. Maher, Dwight Perkins and Schmidt, Garden & Martin designed residencies, schools, and park buildings that mimicked the flat planes of the Midwest prairie—foreshadowing the modern movement to come.

HOW TO IDENTIFY: Prairie School buildings are inspired by the Midwestern landscape, so they often lie low and flat, with broad eaves and an emphasis on horizontality. Their colors and textures are subdued and earthy.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: Robie House (Frank Lloyd Wright), Rath House (George W. Maher), Carl Schurz Public High School (Dwight H. Perkins), Humboldt Park Boathouse Pavilion (Hugh Garden)

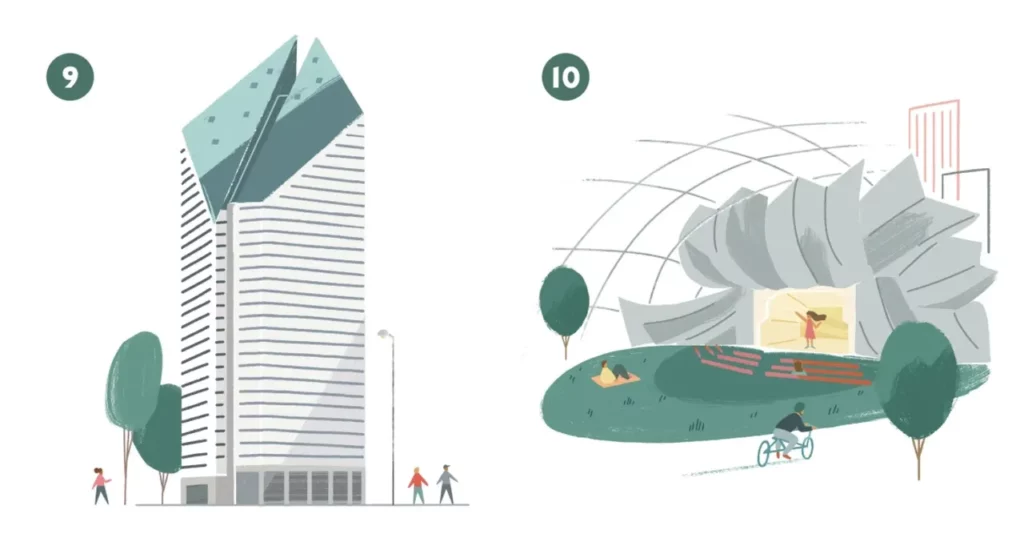

9. Late Modernism

You see Chicago’s Late Modernist buildings in snow globes, and printed on tchotchkes, rubber magnets, and shot glasses. Together, they define Chicago’s skyline (seen in silhouette against Lake Michigan), but are also distinctive enough to be identified on their own (usually on tote bags or coffee mugs). This style includes some big hitters: supertalls like the John Hancock Center and the Willis Tower, the diamond-topped Crain Communications building, the fire engine red CNA Center, and the curvy Lake Point Tower (the only building that’s east of Lake Shore Drive).

HOW TO IDENTIFY: Chicago’s Late Modernist architecture emphasizes shape and pattern rendered in iconic buildings. Like the International Style, glass and steel are the primary materials, but instead of an emphasis on proportion within a grid the emphasis is on the building as a singular designed object.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: John Hancock Center (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill), CNA Center (Graham, Anderson, Probst & White), Willis Tower (Bruce Graham and Fazlur Khan), Crain Communications Building (A. Epstein and Sons), Lake Point Tower (Schipporeit and Heinrich)

10. Millennium Modern

Millennium Park opened in July 2004, over budget and behind schedule, but for Chicagoans, who previously knew the Loop east of Michigan Avenue as a gravel parking lot bisected by railroad tracks, and for visitors from all over the country, the massive civic effort was a shot in the arm for 21st-century Chicago. The park features abstract sculptures (Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate, Jaume Plensa’s Crown Fountain), and Frank Gehry’s outdoor bandshell, which is rendered in cool metal, framed in dramatically feathered bangs, and, set off by a trellis extending the length of the lawn. As the reputation of the park solidified, it had a halo effect, developing a new type of architecture, known as Millennium Modern. The area has become a magnet for international names and has also made international names of Chicago architects like Jeanne Gang. Chicago’s built environment is a test kitchen for supertalls, undulating towers, but also for controversial mega developments like Lincoln Yards and The 78, which are heavily influenced by Millennium Modern. The most creative of these early-aughts structures are our current and future landmarks.

HOW TO IDENTIFY: Millennium Modern architecture developed from a wide range of influences, embracing creativity in terms of building forms and pulling broadly from the natural world, like the waves of Aqua and the curls of the Pritzker Pavilion. Look for curving, metal towers of soaring, serrated glass and heights high enough that they seem to be actually touching the future.

NOTABLE EXAMPLES: NEMA Chicago (Rafael Viñoly), Aqua (Studio Gang), Vista Tower (Studio Gang), Jay Pritzker Pavilion (Frank Gehry), One Bennett Park (Robert A.M. Stern)

See if you can spot the different architectural designs on our Featured Listings page!

By Elizabeth Blasius, Illustrations by Morgan Ramberg for Curbed, 12/5/2019